The last quarter of the 19th century was a busy one for the

police in The Rocks. They moved into a

handsome new purpose built police station designed by the Colonial Architect

James Barnet on George Street. The Rocks Push and other larrikin gangs became

notorious throughout Australia, showing increasing defiance towards the police. Several disease epidemics also occurred,

requiring police to keep the peace and ensure people remained quarantined.

There were also large strikes and riots caused by economic depressions and

union activity that the police had to control.

The Rocks Police also had to deal with increasing xenophobia

towards the Chinese population and accusations from the local community that

they were corrupt. This resulted in a

Royal Commission specifically targeting the professionalism and integrity of

the men of No.4 Station. Despite this two former Police Commissioners, James

Mitchell and Walter Henry Childs, began their careers at The Rocks.

In the 20th century The Rocks Police had to share their

station and then vacate it for the US Naval Shore Patrol and deal with the

beginnings of organised crime. There was also increasing union activity and

protests which they were called on to control. Policing changed dramatically in

the 20th century, and as former Police Commissioner Walter Henry Childs (1872–1964)

said on his retirement:

"I take off my

hat to the policemen of the old days in Sydney, with no equipment, poor

telegraphs, no telephones, slow travelling — it was wonderful how successful

they were.”

Throughout all this time The Rocks Police have had a hard

and emotionally challenging job. The Rocks was a working class neighbourhood

and parts of it displayed crippling poverty and misery. The newspapers of the

time were often reporting on bodies found in the harbour, three in one week

alone, and there are many reports of newborn infants, both dead and alive,

found abandoned in the area. Alcoholism

and violence were extremely common and it was not uncommon for The Rocks Police

to find a body suffering from the effects of either or both.

The new No 4 Station, 127 George Street

In the 1870s a scarlet fever epidemic prompted the

government to appoint the Sydney City and Suburban Sewage and Health Board in 1876 to report

on sub-standard buildings and sanitary conditions. All of the police buildings

in Sydney were inspected, resulting in a rebuilding program which transformed

Sydney’s police stations.

The Harrington Street Watch House not been used since 1847,

leaving the Cumberland Street Watch House as the principal station. It was

condemned in the 1876 Sewerage and Health Board report to the Colonial

Secretary and became so notorious for its dreadful condition that the

newspapers printed articles about it.

Smallpox broke out in Sydney in 1881 and one of the places

reported to be affected was the Cumberland Street Watch House, sealing its fate.

The local police were heavily involved in this epidemic, ensuring people

remained quarantined and supervising inoculations.

|

| Figure 3. Smallpox care in Sydney. Illustrated Sydney News 9 July 1881 |

|

Figure 4. Former police station

copy of tracing from original plans dated 17 July 1880 from Public Works

Department. (Source: 2004 CMP, citing copy held by Sydney Harbour Foreshore

Authority)

|

|

Figure 5. 127 George Street c. 1890, the ‘new No. 4

Police Station’ Sydney Harbour Foreshore Authority Historic Image collection

|

The Cumberland Street Watch House was demolished after the police

moved into their new station at 127 George Street in 1883. It was known as No 4

Station and its new sub-inspector was

Alexander Atwill (1838–1912). He had served in the Royal

Irish Constabulary from 1856 until his departure for Sydney in 1864. On arrival

he immediately joined the NSW Police Force and was stationed at the Cumberland

Street Watch House. Atwill was deployed at the Mint in Macquarie Street from

1870–82 before being appointed sub-inspector in charge of the newly completed

No 4 Station, replacing Samuel Dillon Johnston (1824–1907) who had retired.

Philip Sweeney (1830–96) served with The Rocks police from

1858 until his retirement in 1892. In later years he was the lockup keeper, and

in 1891 Sweeney told the Royal Commission that the station sergeant and the

‘reserve man’ serve 12 hour shifts, from 10am to 10pm, and 10pm to 10am. He said

that women would bring dinners down to their husbands who had been arrested in

Moy Ping’s gambling house[2] and “complain of their husbands spending their money in the gambling houses and

leaving them without food.”[3] The majority of people that Sweeney had to

look after were locked up for drunkenness and gambling. But this gives us in

insight into the running of No 4 Station and the long shifts the police worked.

|

Figure 7. Cartoon by

Norman Lindsay from the Bulletin,

1901, satirising the police.

|

Charges of police corruption 1891–2

Anti-Chinese sentiment was rife in Australia following the gold

rushes of the 1850s. By the 1870s The Rocks had a substantial Chinese

community. The Bulletin maintained an

anti-Chinese stance publishing derogatory cartoons about Chinese reinforcing

these prejudices.[4] In

1891, European business owners in Lower George Street formed The Anti-Chinese

Gambling League claiming that their businesses suffered from the behaviour of

their Chinese neighbours. Alleging filthy, overcrowded houses that were used for

gambling, opium smoking and prostitution, The League claimed that the Chinese

openly solicited the entrance of men and women passing by, creating a cultural

enclave dependent upon police corruption for its continued existence. They

lobbied NSW Parliament until a Royal Commission was appointed.

The Royal Commission

on Alleged Chinese Gambling and Immorality and Charges of Bribery Against

Members of the Police Force [5] largely focussed on The Rocks, where it was alleged the police of No 4 Station

were accepting bribes from the Chinese.

|

Figure 8. Cartoon

commenting on the perceived relationship between The Rocks police and the

operators of Chinese opium and gambling dens. Bulletin, 1890s.

|

Atwill, Sergeant Bartholomew Higgins, and others were

questioned on their dealings with the Chinese community. Higgins was asked to

justify his property portfolio which included almost a dozen buildings in The

Rocks and a block of land at Lane Cove. Sub-Inspector

Atwill had undoubtedly made enemies during more than 30 years as a policeman.

At the Commission he had been accused of:

(1) taking receipt of a bookcase at no cost

from Ah Toy, cabinet maker of Lower George St in 1891, (2) demanded a present

of £100 from a publican, (3) had said to a photographer that he should supply

photographs freely of himself and his family, and that other tradesmen in the

area should likewise supply goods “in consideration of the protection he

afforded them”, (4) induced a shopkeeper (Dawson) to smuggle a quantity of tobacco and

cigars ashore for his personal use.[6]

The Commission found that all of the allegations against the

police were baseless.

Police death in the course of duty

Senior Constable Henry Murrow (1869–1897) of No 4 Station

died from an injury received on duty. Born in England, Murrow had settled with

his parents in New Zealand where he joined the New Zealand Police Force before

moving to Sydney and joining the NSW Police Force in 1883.

On 4 October 1897, Murrow, while on duty in The Rocks was

hailed by Jane Jones, publican of the Orient Hotel who was having trouble with

a drunken patron, Daniel Conway. Jones asked Murrow to move Conway along. This

he did, requesting that Conway

go home. Conway left with another man, walking south along George Street,

closely followed by Murrow, as witnessed by George Howlett. Nearing the Port

Jackson Hotel (now the Russell Hotel) on the corner of Globe Street, Conway’s

companion was swearing, at which point Murrow overtook them and clasped his

hand on the man’s shoulder. This resulted in a fight during which Murrow struck

his head on the woodblock paving of George Street. Howlett intervened, helping

Murrow to his feet. Conway then fled back towards Argyle Street and Howlett

assisted Murrow to the nearby No 4 Police Station.

Murrow was escorted to Sydney Hospital where wound was

dressed. It appeared to be minor so Murrow was dismissed. Meanwhile Conway was

delivered into the custody of water police Constable William Cleugh who took him

to the Water Police Station in Phillip Street where he was charged with

assaulting Morrow while he was on duty.

At 10.30pm at his home at Paddington, Murrow lost

consciousness and died around 12.30am. Doctors were summoned and determined

that he had concussion, an autopsy confirmed it. Conway, was charged with

murder but convicted on the lesser charge of manslaughter and sentenced to six

months hard labour at Darlinghurst Gaol.[9]

|

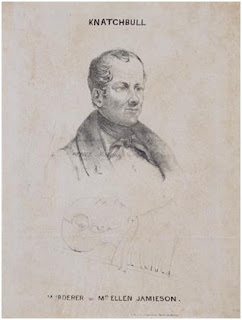

Figure 9. Daniel

Conway, photographed in 1897 at Darlinghurst Gaol for the manslaughter of

Constable Henry Murrow of No 4 Station. (NSW State Records NRS 2138, photo

7218)

|

The pushes

The Rocks Push became one of Australia’s most well known

street gangs, made up of ‘larrikins’, young unruly men without respect for

authority. They were not the only gang in the area, there was also the Millers

Point Push, the Argyle Cut Push, the Green Push made up of Catholics and the

Orange Push comprising Protestants. As well as fighting among themselves the

pushes also had battles with others around Sydney, such as the Glebe Push, the

Straw Hat Push, the Forty Thieves from Surry Hills and the Gibb Street Mob.

The Rocks push became famous or infamous for several

reasons, their leader, or captain, was Albert Griffiths, popularly known at the

time as “Young Griffo” who became the world featherweight boxing champion in

1890. Fighting skill was essential to lead these gangs and Larry Foley, another

famous boxer, was the captain of the Green Push.

|

Figure 10. Young Griffo (Wikipedia)

|

|

Figure 11. Larry Foley (NLA http://nla.gov.au/nla.pic-vn3060380)

|

The Rocks Push was known

for their specialty for robbing people unfamiliar with the area. They also

engaged in union activity and riots, such as the riot at the ASN Company

offices in George Street in 1878, which the Police had to break up with horses

and batons.

|

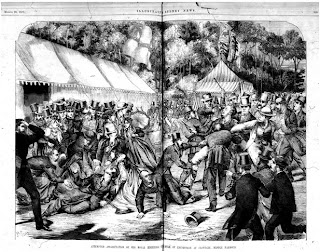

| Figure 12. The 1878-9 Maritime Workers Strike, the riot in George Street. (Ref unknown possibly Illustrated Sydney news) |

During the early 1890s they intimidated men finding work at

the Labour Bureau, objecting that these men were strike breakers and lowered

working conditions. The push was

responsible for kicking to death at least two sailors, but it will remain

unknown how many other people were robbed and assaulted by them. Several of their members were flogged for

throwing blue metal at police and knocking one unconscious. They appear to remain a force in the area

until the outbreak of World War 1.

|

Figure 13. The Bulletin 9 June 1900

suggesting London Police could help with the problems of the pushes. (Scanned

by SHFA from Microfiche University of Sydney Fisher Library)

|

|

Figure 14. Reginald Lloyd Holmes

(Scratching Sydney’s Surface http://scratchingsydneyssurface.wordpress.com/2009/02/22/20-feb-09-shark-arms/)

|

The other murder occurred in 1956 in broad daylight outside

the Australian Hotel in Cumberland Street. The sheer audacity of the crime led police to

believe that it was an organised hit, however no one has ever been

charged. A plaque has been placed on the

pub that reads:

"John William Manners was shot dead outside The

Australian Hotel on June 8 1956. George Joseph Hacket was detained for Manners

murder but was acquitted of the crime at the Central Criminal Court on October

25 1956. No one since has been tried for John Manners' murder"

In December 1941 the United States entered the Second World War and following the fall of the Philippines, General Douglas Macarthur relocated to Australia. Sydney became a major supply base for the operations, and an important naval base for the repair of US Naval ships.

|

Figure 15.

US Navy coming ashore at Dawes Point. (Mitchell Library GPO_49699)

|

The United States Navy Shore Patrol took over use of the

five cells and both exercise yards from 29 July 1942, and then on 8 March 1943

the entire building. The purpose was to ensure order among US Naval personnel

while on shore leave

The Sydney Morning

Herald carried a brief report of an escape from 127 George Street on 2

November 1942:

U.S. SAILORS ESCAPE FROM LOCK-UP

Four American sailors escaped from

the George Street North police station yesterday afternoon by smashing the iron

grille over the exercise yard. Openings were made between the bars large enough

for them to squeeze through. The sailors were being held in custody by the U.S.

Navy shore patrol, and police were asked to assist in recapturing them.

The necessity for a shore patrol is illustrated by another

episode, reported by the Sydney Morning

Herald on 9 May 1944:

Man Wounded by U.S. Patrol

Three shots were fired by a member

of the U.S. Navy shore patrol in George Street, near the. Victory Theatre, at

1.15 last night after two naval ratings had escaped from the patrol wagon. One

bullet ricocheted from a wall and struck George Wilbur Woody, a U.S. Navy

storekeeper, who was standing in a big crowd outside the theatre. Police officers

consider that it was a fortunate chance that other persons in the crowd were

not struck by the .38 bullets.

In August 2009 in the roof space above the northern cells a

series of artefacts relating to the United States Navy’s use of the building

were found. They were a number of cigarette and chewing gum packets, a ciphered

telegram, match boxes, a tinware dish, and pages of newspapers from 8–10

October 1942.

The three green Lucky Strike cigarette packets have US Sea

Stores Custom labels, confirming that they arrived via the US Navy supply

system. Lucky Strike changed their packaging from green to white in 1942, and

so these packets date to the first year of the US Navy’s occupation of the

building. After 1941, to

protect the reputation of its brands after supplies of top-grade ingredients

became limited, the company took Wrigley's Spearmint, Doublemint and Juicy

Fruit off the civilian market and the entire production was sent to the

troops. The artefacts were all in

close association and were probably all deposited at the same time, although

what someone was doing in the roof space is still a mystery. It is unlikely that the escapees reported in

November 1942 were held for a month in these cells.

|

Figure 16.

Artefacts found above cells in former Police Station 2009. SHFA

|

Traffic Police

(1950–74)

On 11 March 1950 127 George Street was resumed by the NSW

Police as offices, and the whole building occupied by the Traffic Division of

No 4 Station, which included the Special Parking Police. The main station

continued to be based at Phillip Street until 1983.

In 1900 the control of traffic came under the jurisdiction

of the NSW Police, largely due to the introduction of electric tramways in

Sydney which shared the public streets with horse-drawn vehicles and

pedestrians.

|

Figure 17. A constable from No 4 Station on traffic patrol

(centre, in white helmet) in Hunter Street, c. 1905. (Mitchell Library GPO 1

34744)

|

Traffic patrol had been a part of No 4 Station for some

time. Indeed, one of the earliest casualties of the electric trams was

Constable Black:

When on duty at the corner of

George-street and Circular Quay on Saturday morning Constable Black, of No 4

Police Station, became jammed between two passing trams. One of the cars struck

him heavily, fracturing two of his ribs and inflicting other injuries to the

body. Black, who lives in Argyle-street, Miller's Point, was removed by the

Australian Ambulance to Sydney Hospital, where he received treatm

The increase in car ownership had put a heavy strain on the

streets of Sydney, designed as they originally were for foot, or at best horse

drawn transport. Electric trams and cars appeared around the same time. By the

1930s car traffic congestion was becoming a problem in Sydney, and in 1937

there was talk of phasing out trams, and extending the public bus service.

Postponed by the intervention of World War II, it was not until the early 1950s

that the scheme was put into action[12].

Trams were gone from Sydney by the end of 1961.

Traffic lights were introduced to London in May 1933.[13] Five months later Sydney’s commenced operation at the corner of Kent and Market

streets.[14] Gradually mechanisation relieved the police of general point duty at

intersections. Technology and regulations took much of the professional police

roll out of the Traffic Police. Gradually the role of traffic police was taken

over by clerical staff attached to the Police Forc

On 2 November 1974 the NSW Police Force finally vacated 127

George Street, handing it over to the Sydney Cove Redevelopment Authority

(SCRA). The Traffic Police relocated to another SCRA building; 16–18 Grosvenor

Street, along with the Police Records Division. In 1983 the police returned to

The Rocks (renamed The Rocks Local Area Command) following the closure of the

Phillip Street Station (now the Justice and Police Museum). The former ASNCo

Hotel at 91 George Street was leased from SCRA and refurbished for their use.

They remained here until moving to larger premises across the street at 132

George Street in 1997 where they still remain. The NSW Police can therefore

demonstrate a presence of more than 200 years in The Rocks, 92 years of which were

spent at 127 George Street. There are five extant buildings in The Rocks that

have served as police premises; Cadman’s Cottage (Water Police 1847–58), 127–129

George Street (No 4 Station 1882–1974), 16–18 Grosvenor Street (Traffic and Records

1974–90), 91 George Street (1983–97) and 132 George Street (1997 – present).

[1] CGC

p458

[2] Moy

Ping lived in Harrington Street in the 1870–80s and operated as a merchant from

208 George Street.

[3] CGC

p267

[4] See Fitzgerald, S. (1997): Red Tape Gold Scissors (State Library of NSW) and Lydon, J. (1999): Many Inventions: the Chinese in the Rocks, Sydney, 1890–1930. (Monash Publications in History)

[5] CGC

[6] CGC p23

[7] SMH 6 Oct 1884, p6

[8] John Kearney: Register of Police Appointments (NSW State Records).

[9] Daily Telegraph, 7 and 8 October 1897.

[10] The NSW Police Property Cards for the building detail changes to the building from 1915–1974. The transferral of the head station to Phillip Street in 1933 would have meant an overall increase in cell accommodation, although a police presence was maintained at 127 George Street up until 1943 when the US Navy took over all of the building. From 1950 the Traffic and Special Parking Police would have had little, if any, use for cell accommodation. It is likely therefore that the two rooms were converted to cells during the US Navy’s occupation from 1942 – c. 47, and therefore the action failed to be recorded in the NSW Police’s property cards.

[11] SMH 9 Sept 1901, p8

[12] SMH 26 May 1953, p2

[13] SMH 13 May 1933, p18

[14] SMH 13 Oct 1933, p11

[15] In 1996 the State Debt Recovery Office relieved the NSW Police of the task altogether.