"appoint constables and other necessary officers and ministers in our said territory and its dependencies for the better administration of justice and putting the law in execution".

However, policing in Britain was less than proficient, so he had no model to base the establishment of a law enforcement agency upon.

Watchmen, called Charlies after King Charles II who introduced them, were the first paid keepers of the peace in London, but they were rather ineffectual and it was a job for old men.

Charlies were often ridiculed by the people of London. The Bow Street Runners were formed in 1748 and they have been credited as Britain’s first professional police force. In 1829, Robert Peel established the Metropolitan Police of London. They became known as Bobbies, a name that has stuck with English Police.

Figure 1. ‘Tom Getting the Best of A Charley’. George Cruikshank 1820. Museum of London Prints.

The Royal Marines who accompanied the First Fleet refused to carry out the duties of a police force. Their commander, Major Robert Ross, stated that his men were soldiers, not prison guards, and it was insulting to His Majesty’s Regiments to expect them to act in such a role. They did agree to guard the settlement and patrol at night.

Governor Phillip appointed freeman James Smith as a ‘peace officer’ but he retired after a brief period, he was deemed too old and infirm to be effective.

By 1789, scarcely a night passed when there was not a theft of some kind. After six marines were executed in March 1789 for stealing provisions when the colony was close to starvation, it became obvious that some form of organised law enforcement was needed.

In July 1789, convict John Harris went to Collins with a proposal for a night watch to be established from among the convicts to deal with all those found away from their huts at "improper hours". Collins commented that:

"It was to be wished, that a watch established for the preservation of public and private property had been formed of free people, and that necessity had not compelled us in selecting the first members of our little police, to be appointed from a body of men in whose eyes, it could not be denied, the property of individuals had never been sacred. But there was not any choice convicts who had any property were themselves interested in defeating such practises [as theft]".

This first night watch consisted of 12 well-behaved convicts and was split into four divisions. The Rocks watch patrolled from the hospital to the observatory, approximately Globe Street to Dawes Point. In November 1789, Collins wrote that the night watch had been very effective, there were fewer crimes and the culprits were usually caught.

On 1 February 1790, Governor Phillip advised Lord Sydney of "the institution of a night watch to control robberies (particularly of vegetables and poultry) was immediately effective” and that there was “no robbery in three months". The night watch were held in "fear and detestation" by their fellow convicts. Convicted pick-pocket George Barrington arrived in Sydney in 1791 and was almost immediately appointed a police constable guarding the colony’s stores. He later became Chief Constable at Parramatta.

Figure 2. ‘Barrington Detected Picking the Pocket of Prince Orlow’, 1790, by Inigo Barlow. Rex Nan Kivell Collection, National Library of Australia.

During 1789, Governor Phillip also formed a row boat guard whose primary duties were to police the harbour and foreshores of Sydney Cove to detect smuggling and prevent the passing of letters between convicts and crews of sailing vessels at anchor. As a fore-runner to the water police, the row boat guard was a policing organisation that would have a long association with The Rocks.

In response to growing public disorder and the difficulty in policing an expanding city, Governor Hunter divided the town of Sydney into four divisions and directed residents to number their houses; each division elected and paid for their own watchmen who were instructed to report drunkenness, gambling and loitering. To discourage and locate absconding convicts, they were also empowered to request identification from people outside the division of their residence.

As the colony grew, so did the duties and size of its fledgling police force. The Sydney Foot Police Force was established in 1790, there were 36 Constables serving by 1800. The Sydney Foot Police Force continued as an organised force (later known as Sydney Police) until the amalgamation of all New South Wales colonial police forces in 1862. The Row Boat Guard was at various times, both an independent water police and also part of Sydney Police.

In 1803, the first death of a police officer in NSW occurred when Constable Joseph Luker was beaten to death with his own cutlass, two of his fellow constables were suspected of the death but it was never proven. The one man who did face the hangman’s noose was reprieved after three attempts to hang him failed.

Figure 3. ‘The Death of Constable Luker’. Pen and ink by Danny Webster, 2003

In 1810, Governor Macquarie re-organised the police force and changed the division of the town into five districts, each to have a watch house and district constable. Six watch houses were built within Sydney’s five metropolitan police districts.

The Rocks was divided into two districts separated by Globe Street, the original boundary of the night watch; watch houses were built soon after in Cumberland and Harrington streets.

The Harrington Street building, in all likelihood, stood directly behind 127 George Street, where a replacement was constructed in 1829 and which stood until 1911.

The original Cumberland Street watch house is believed to have been at 188 Cumberland Street until it was replaced by another opposite the site of Lilyvale (176 Cumberland Street) in 1829 . The second Cumberland Street watch house served as the principal station for Sydney north district from 1847 until it was replaced by the property at 127 George Street in 1882.

Figure 4. The Harrington Street watch house, photographed c. 1882; it has been misidentified as the Cumberland Street watch house. From SHFA Historic Image Collection.

Ex-convicts still dominated the police in the 1820s according to Alexander Harris: “....at this time almost every constable in Sydney and indeed in the colony had been a prisoner of the crown; I believe there were two or three old soldiers in the force, but their principals were not a whit superior, so far as I heard and observed, to those of the convict class."

The competence of watchmen was often called into question, and reported on in the press. All the appointments and dismissals, and their reasons why were published.

There were numerous articles on constables around The Rocks being asleep or drunk on duty, and people being locked up for drunkenness losing their valuables. The constables were mostly ex-convicts and it paid to become one—at least in rum, as a constable was issued with two gallons of rum and the chief constable received five gallons.

As maligned as they were, the police in The Rocks in those early years had a really tough job. They received no training, were enormously disliked, especially by other ex-convicts who saw them as class traitors, and they had to police a neighbourhood that wasn’t known for its law-abiding population, or respect for authority.

Even so, these constables and their families lived in The Rocks and were an integral part of the community they policed.

In 1833, the Sydney Police Force was established with 84 men, by 1839 the number of police increased to 128.

In the early 1840s transportation to NSW ceased and Sydney became incorporated as a city.

For the Sydney Foot Police, this meant a reduction in numbers and wages as they were being paid by the city and not the colonial government. These cuts started to show with only 89 constables remaining by 1843. The following year their wages were again reduced to three shillings a day. The newly incorporated City of Sydney Council of 1843 was unable to levy rates needed to pay police officers now under their control.

In 1844, the citizens of Sydney had a public meeting requesting the increase of police numbers. One of the points they raised was that from Dawes Point to Pitt Street there was ‘scarcely any property that was not committed to the protection of private watchmen and the reason was there were not enough policemen’. They believed the numbers of ex-convicts from Van Diemans Land and Norfolk Island moving into the city made an increase in police numbers a necessity. There had also been two horrendous murders in The Rocks that year.

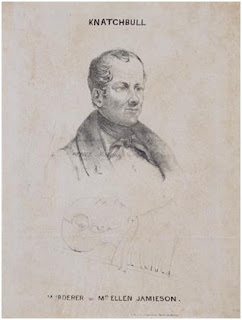

One was committed by John Knatchbull, a Norfolk Island expiree, with a ticket of leave, who was the brother of Sir Edward Knatchbull. He went into the shop of a poor widow, named Ellen Jamieson. While she was serving him, he bashed her head in with a tomahawk. She died a few days later, leaving two orphan children. Knatchbull was hung at Taylor Square in front of a crowd of 10,000 people. His brother sent money to educate the children.

Figure 5. John Knatchbull. c.1844 Artist unknown. From National Portrait Gallery

The other victim was Thomas Warne, whose was murdered by his valet. This murder was discovered when Warne’s partly burned and dismembered body spilled out of a barrel on George Street as the valet was trying to dispose of it. He had raised suspicion by attempting to employ some watermen to take the barrel into the harbour and dump it, telling them it contained pork which had gone bad.

The demographic of The Rocks in the 1840s started to change. There were less convicts assigned to The Rocks, free immigrants and Australian-born residents became a larger part of the population and ex-convicts were older with jobs, homes and families.

That’s not to say that the place was heaven to police; it was a port town and they can get pretty rowdy. Sailors started riots on several occasions; two of the most notorious were in 1841 and 1851. In both instances the watch houses came under attack and were almost destroyed.

Figure 6. Harrington Street Watch House building. Although the Harrington St Watch House ceased functioning as such in the 1840s the building remained until c. 1911. It is in the centre of the image above marked with the “X”. From SHFA Historic Image Collection.

In 1850, all the police units, including the Sydney Foot Police, the Water Police, and Mounted Police , came under the New South Wales Police Regulation Act which placed all police NSW under the control of an inspector general. But two years later, the Act was rejected by the British Parliament and the inspector general's power was reduced to the County of Cumberland and control of the Mounted Police in the country areas.

In the 1850s, the gold rushes began.

In The Rocks this meant a flood of immigrants into and through the area including Chinese, many of who started businesses. The need for police everywhere rose so the Police Recruiting Act, 1853 was passed.

As a result, men were recruited from police forces in England, Ireland, Wales and Scotland. Free passage to Australia was exchanged for a minimum of three years service. These men started to land in Sydney in 1855. One of the first was John Taylor, formerly of the London Police; on arrival he was immediately appointed sergeant. He became senior sergeant in 1862, and was acting sub inspector in 1870. In 1875, Taylor was sub-inspector of the Cumberland Street Watch House.

The NSW Police Force was reorganised in 1862, as were the police districts. The Cumberland Street Watch House became the principal station for No. 4 Metropolitan Station. No. 4 district had jurisdiction over Balmain, the North Shore, Lane Cove, Manly and the Water Police. A total of 44 officers were assigned to No. 4 in 1875; 21 at The Rocks, 14 at Water Police, four at Balmain, three at North Shore, and one each at Manly and Lane Cove.

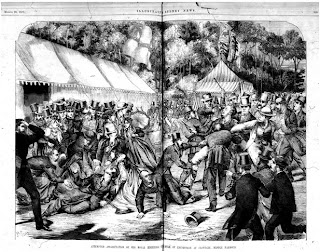

In 1868, the No. 4 district police had to investigate the attempted assignation of Prince Alfred, the Duke of Edinburgh, at a picnic in Clontarf. The picnic was a fundraiser for the Sailors’ Home, which is located in The Rocks.

The shooting caused an enormous uproar; the suspect was Irishman Henry James O’Farrell. Although it was alleged O’Farrell was a Fenian, he had actually only recently been released from the Tarban Creek Lunatic Asylum at Gladesville.

This was the first visit to Australia by a member of the royal family so the pressure was on the police as the entire country was watching. The population reacted with shock, embarrassment and shame.

O’Farrell’s crime touched off a long and often bitterly waged vendetta against Irish nationalists, their sympathisers and the Irish generally. This must have made it tough for The Rocks Police, who had numerous Irishmen in their ranks.

Figure 7. Attempted assassination of his Royal Highness the Duke of Edinburgh at Clontarf, Middle Harbour. Illustrated Sydney News 25 March 1868.

Over the years, The Rocks Police had become dominated by men recruited from the UK, especially Ireland. Between 1860 and 1890, at least 23 police in The Rocks were Irish and 10 of them had served in the Royal Irish Constabulary.

There were also at least 11 Scots, 10 Englishmen and eight Australians, of these nine had served in other police forces and three in the military. These experienced police made an impact: from media reports alone The Rocks Police were considered more professional, reflecting the difference between recruiting from convicts and experienced police.

In 1876, the Cumberland Street Watch House was condemned as being in an appalling state by the Sewage & Health Board which recommended that it be demolished.

Detainees could not be kept there because of the conditions, instead they were taken to the Water Police Cells in Cadman’s Cottage. Eventually the Cumberland Street Watch House was demolished and The Rocks Police moved into their handsome new station at 127 George Street in 1883.

Figure 8. The Cumberland Street Watch House designed by William Dumeresq. From Illustrated Australasian News, 29 June 1881.

[1] From Pierce Eganâ's Life in London; or, The Day and Night Scenes of Jerry Hawthorn, Esq. and his elegant friend Corinthian Tom, accompanied by Bob Logic, The Oxonian, in their Rambles and Sprees through the Metropolis, (1820-1821).

[2] Many websites, including that of the NSW Police name John Smith as the first constable, this is incorrect. First Fleet Journals including Phillip, Tench and Collins all state that James Smith was appointed as a “Peace Officer”. James Smith was the only free settler on the First Fleet, he paid his way and his presence was not known to Phillip until they reached the Cape of Good Hope. Smith came out to try his luck in the new colony and had the backup plan of going to India if the new settlement didn’t provide the opportunities he wanted.

[3] From: Website In the Line of Duty, Policing in Australia since 1788. Visited 18 June 2012. http://www.inthelineofduty.com.au/timeline.asp?startyear=1803&showstate=all&direction=next

[4] The site of the second (1829) Cumberland St watch house is now beneath the Bradfield Highway, the approach for Sydney Harbour Bridge.

[5] Votes and Proceedings of the NSW Legislative Assembly, 1875: Police (Distribution of Force on 1 December 1875).